This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on Friday, August 25, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

Times were tough in 1918, wherever you were. Besides those dodging World War I battles in Europe, the whole world was dodging waves of the flu. Although records of the time are incomplete, E. O. Jordan’s book Epidemic Influenza (1927) carried estimates that within a few months as many as 20 million people perished, including 548,000 in America. Jordan speculated that as many as 50 times that number were sick, ranking the siege “with the plague of Justinian and the Black Death as one of the severest holocausts ever encountered.” The flu was far deadlier than the war, estimated to have cost only some eight-and-one-half million people between both sides.

Aside from a colder-than-usual winter in the Garland/Mesquite area, few seemed overly preoccupied with health until October, when people started coming down with a malady that felt like flu but killed like pneumonia. So says Mrs. Nell Jack, a 97-year-old Garland native who escaped the scourge, despite taking time off from classes at SMU to tend the sick. “Around here they called it everything from Spanish flu to pneumonia, but if you died, and a lot did, it didn’t make much difference what you called it,” she added.

Her friend, Fern Handley Thompson, who claimed she was always “sickly” back then, caught the disease, as did her parents and a cousin, but survived into her 99th year to tell about it. In the 1986 Storer Cable series Garland Perspectives, Mrs. Thompson recalled that the cousin stayed with them in the dining room, but she herself was quarantined for the duration in the same bedroom with her mother and her father, Peter Handley, who owned a drugstore in town. That duration, according to Mrs. Jack, was at least two weeks of feverish prostration with hacking, aching misery, after which doctors sternly warned against overexertion and cold air. “Some may have taken aspirin, but we had no penicillin or other fancy medicines back then,” she said, “so all we could do was rest, drink all the liquid we could keep down and hope for the best”.

W. A. Holford, who had just purchased The Garland News for the second time, succeeded publisher Z. Starr Armstrong, son of Dr. J. C. Armstrong, one of the local physicians battling the flu outbreak. Amid the health crisis, Mrs. Holford’s paper carried an increasing amount of advertising for patent medicines, including Calomel, which Mrs. Thompson took for almost everything and Mrs. Jack believed to be poisonous. Calomel’s head-on competitor was Dodson‘s Liver Tonic, whose ads warned that “Calomel loses you a day’s work.”

Also popular was Penslar, “a dynamic tonic for headache, irritability, mental depression, sudden fits of temper, inability to think clearly, loss of memory and continued melancholy,” at $1.50 per bottle. “Weak or thin blood” could be treated with Grove’s Tasteless Chill Tonic for only 60 cents a bottle. Advertisers claimed that for 50 cents a bottle Herbine “cleanses the liver of bile, sweetens the breath, purifies the bowels, corrects dizziness [and] restores energy and cheerful spirits.” Alcohol content in these potions, if any, was not specified.

Whereas Armstrong had posted advertisements on the front page of the News, Holford began to use the prime space for local news items and obituaries (which were multiplying fast by November), anchored around a list of additions to his new $10 lifetime subscription plan. Holford family members later contended that the plan was an optimistic effort to build capital for first-class equipment, but skeptics have wondered if it coincidentally enrolled subscribers in advance of fatal flu attacks. Although Garland’s incorporated area contained less than 1,000 souls, added demand from outlying areas had catapulted weekly News circulation to more than 1,600 copies during the fall of 1918. In November, when Garland’s first WW I casualty was reported, Holford ran eight obituary notices and extended the “deadline” for lifetime subscriptions.

Public officials were so concerned that in October, Garland Mayor George A. Alexander, who also sold life insurance, had convened a special Saturday afternoon council session for the purpose of prohibiting public gatherings. School classes were suspended and church attendance dwindled, save for prayers of deliverance. Because he had heard that it might prevent the flu, D. Cecil Williams, a local undertaker, was rumored to have begun chewing tobacco while working overtime with victims in the family’s mortuary.

News accounts suggest that even swine began to exhibit flu-like symptoms, much worse than their more common attacks of epizootic and occasional bouts with tuberculosis, so that authorities recommended isolating hog houses. Today, certain old-timers and their decedents sometimes still classify the human cold/flu syndrome as an attack of “the epizooty”.

Since there were no public reports or death certificates required here at the time, and authorities may have soft-peddled news to protect the war effort, the exact local cost of the 1918 fall flu epidemic is impossible to determine. But in December, mostly of its own accord, the epidemic subsided as quickly and quietly as it had begun, and by New Year’s Day young Williams had tapered off chewing tobacco.

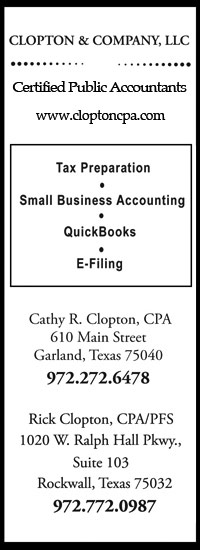

Photo not available

Photo Caption: The Handley Drug Store, as photographed about 1926 on the west side of the Garland square, had a full stock but few remedies for the disastrous flu epidemic of 1918.

Photo courtesy Gary Engleman and the Garland Landmark Museum.