Donate

Please consider supporting our efforts to preserve Garland's history by donating here:

See More

Schools, Sports, Entertainment

Schools, Sports, Entertainment

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on December 1, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

Garland’s Plaza Theatre was once the flagship of a five-unit movie combine owned and operated by Harold R. Bisby and his wife Jennie. There was no business like “picture-show” business, and besides their three locations in Garland, the couple operated The Plaza Theatre in Rockwall and The Wylie Theatre as well. Theirs was the primary entertainment game in the entire area.

The Bisbys, he raised in Kansas and she in Iowa, had settled in Garland in 1937, arriving with decades of entertainment industry experience between them. Their first venture was the Garland Theatre at 618 Bankhead (now Main Street). By 1941 they had begun construction of the Plaza, located at the northwest corner of the town square, from a 1918-vintage structure formerly occupied by the Cole & Davis dry goods establishment. Their third Garland site, the Texan Theatre at 510 Bankhead, opened in 1947.

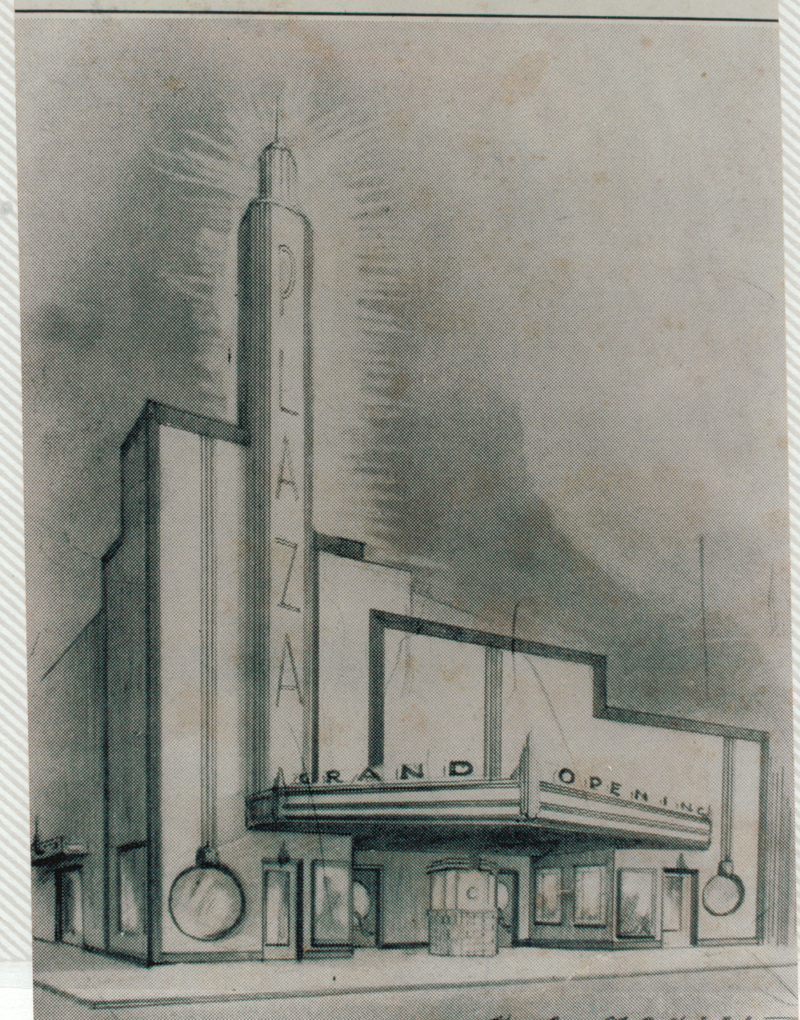

Commissioned to design the original Plaza was H. A. Manzer, a veteran local lumber dealer who dabbled in architecture and other artistic pursuits. Mr. Manzer created a classic Art Deco facade, employing ornamental stucco and maroon colored glass, for the 50-by-140-foot structure. Flanking the central ticket booth on either side of the doorway were spaces for small shops, and, inside, a balcony was created to expand seating area for 700 persons. Although no cost figures were published for the private venture, the Bisbys proclaimed that the Plaza was equal to any $50,000 theater in the state.

Opening night was April 4, 1941, Garland’s 50th birthday, and almost every ambulatory person in the town of 2,500 showed up at one time or another during the day. Featured was a showing of Western Union, starring Robert Young and Randolph Scott. Both Clint Sutherland’s portrait studio and Ms. Clem Murphree’s dress shop occupied the theatre shops.

Staffing the theatre were corps of local residents, including high school students, many of whom encountered their first business experience under the watchful eye of Jennie Bisby. One of these staffers between 1945 and 1948 was Bill Holmes, who rose through the ranks from usher to popcorn popper to projectionist. Although he describes his pay as uninspiring, he admits ready access to the concession booth and still recalls that there were 164 kernels in the average nickel bag of Plaza popcorn. In unsupervised slack time the future chemical engineer also conducted scientific experiments by setting fire to one end of a film reel, which was rolled across the street for a momentary line of flame to test the response time of I. H. Huffaker, Garland’s only patrolman in those days.

During 1948 the Bisbys added a ”Polar Air” refrigeration system to the Plaza. Compressors for this early air conditioning were positioned in a basement well beneath the projection stage, and signs with a polar bear emblem appeared on the front of the building. On occasions when the machinery was reluctant to function, hammer blows about the compressors usually coaxed them into action.

In 1950, the building was remodeled again, stem to stern, this time designed by Dallas architect Jack Corgan. Walking over new terrazzo past the Denzil Graves mural of ballet dancers in a Cindarella motif, opening-night patrons enjoyed leather seating, high-intensity arc lamp projection and an added “cry room” for noisy children, while they viewed the film Thelma Jordan, with Barbara Stanwick and Wendell Corey. Cartoons for the evening featured Bugs Bunny and Pluto, and Mr. Bisby reiterated that management’s objective was to “provide for Garland only the best of clean, wholesome family entertainment.” Nevertheless, many younger couples continued to become better acquainted in the private shadows of the Plaza.

By the late 1950s, with many of Garland’s 25,000-plus residents now developing affection for their television sets, the Bisbys had withdrawn from active theater management to pursue their many civic interests full-time. The Plaza was subsequently leased to a series of entertainment occupants, and over time the building fell into disrepair. Most of the roofing material had already collapsed and floated downstage when John Skelton, trustee of the Bisby estate, donated the property to the City of Garland in 1992.

After a major cleanup that year by employees of Garland Power and Light, the Garland Cultural Arts Commission, appointed by the City Council and assigned administrative oversight of the facility, secured a $120,000 federal funds grant to clean out asbestos, repair the roof structure and install new roofing. Since that work was completed in 1994, the Plaza has been mothballed in dry-shell form, awaiting future renovation as a multi-purpose civic center providing needed meeting and assembly space for the city.

Rendering by H. A. Manzer of the original Art Deco facade of the Plaza Theater on the Garland square.

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on November 17, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

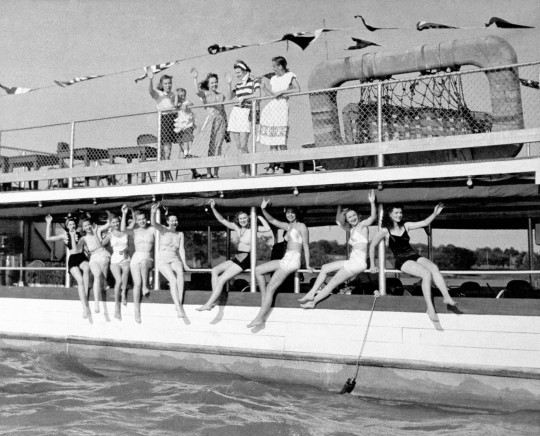

Some of the surplus materiel from World War II was quickly recycled into the Bonnie Barge, a familiar party and dance boat that ploughed the waters of White Rock Lake from 1946 to 1956.

John H. (Johnny) Williams Sr., a Garland native, fashioned the double-decker craft in 1945 from two military pontoon boats fastened side-by-side. Constructed entirely of cold steel and eventually powered by a Chrysler Sea Mule Engine, the barge was affectionately named after Mr. Williams’ wife, Bonnie, a Rose Hill community product, who was gracious enough to help operate it for hire.

Although possibilities for the lake had been discussed as early as 1884, it was 1914 before 5.8 billion gallons of water from White Rock Creek filled the basin behind a new dam and spillway. The original objective for the project had been to assure Dallas an indefinite water supply, and 2,292 acres were accumulated at a cost of $176,429 to accommodate the effects of the costlier $260,000 dam and spillway. But priceless recreational benefits began accruing immediately, not only for Dallasites, but also for residents of Garland, Mesquite and surrounding towns for whom it was then the closest lake of any size.

Uses for the lake became Dallas political issues, as enthusiastic proponents of a Coney Island atmosphere collided with suspicious owners of luxury lake-view homes that gradually rose around the perimeter of White Rock. For a time, until they were finally rooted out by the city, small recreational cabins clustered about on leased sections of the shoreline. At another lakeside site, Dallas maintained a prison farm known as the Pea Patch, where prisoners could work out fines for drunkenness and other non-violent offenses. A Civilian Conservation Corps camp was located there during the 1930s. Yet by 1938, Dallas Morning News writer Paul Crume reported in an article that “the National Park Service rated White Rock Lake as possibly the most used municipal playground in the nation.”

Little of this escaped the entrepreneurial mind of Johnny Williams, who had lost a leg in a youthful motorcycle accident, but later won swimming contests and walked on crutches at a faster clip than the average biped. He and his wife had begun their aquatic entertainment ventures on White Rock in 1937, offering speedboat rides on the lake for 25 cents a head. Although inflation eventually drove the price up to 50 cents, the little runabouts stayed full of passengers.

The barge offered an added entertainment dimension, wherein dozens of people could congregate on each of the two floors, enjoying snacks and soft refreshments from the boat facilities or sharing whatever they brought on board. The season extended from April 1to November 1, and rarely did she fail to book a night’s fee of $54 on weekdays and $64 on weekends. In severe weather, the barge hugged the dock while the parties went on.

Johnny Williams Jr., who literally grew up on the lake, was required by city ordinance to have an adult on board when he piloted either the runabouts or the barge before his eighteenth birthday. “We always had responsible passengers that ranged from church groups to fraternities.” said Williams. “Even Billy Graham partied on the Bonnie Barge.”

By 1956 the city had decided to eliminate speedboats of more than 10 horsepower, but allow the popular barge to remain. “My Dad felt like the speedboats were insurance for the barge in case it got into trouble, so when they went, the barge went,” explained the younger Mr. Williams.

For awhile the Bonnie Barge rested in a pasture on Rose Hill Road, then she was pared down to a smaller size. The last time any of the Williams family saw what was left of her, she was dredging mud on Lake Dallas.

Photo Captions: .

The Bonnie Barge, a double-decker party craft, docked at White Rock Lake about 1952.

2. Johnny Williams, Sr. and his wife Bonnie aboard one of their rental speedboats.

3. Although the Bonnie Barge catered to a wide variety of church groups, this party was different. (bathing beauties)

Photos courtesy Johnny Williams, Jr.

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on December 22, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

The roots of contemporary live theatre in Garland run decades into the city’s past

Aside from the usual drama created by local preachers, politicians and school pupils, literary readings were common before the turn of the century. Eventually, certain organizations began staging periodic benefit performances of various types as fundraisers for other activities.

But in 1935 an aspiring group of local amateurs convened solely for a serious attempt with at least one adult play in the Garland High School Auditorium, then located on the site of the present Central School campus. Although few records are extant, surviving veterans of that company report that its produce/director was Joe Smith Dyer and that H. A. “Hap” Manzer created the sets. Beyond that, each remembered being in one play, but after 60 years none could compare titles to determine the exact number of productions. Mattie Nicholson Markley, however, remembers being blinded by the lights and falling off the stage of whatever play it was that she appeared in. Apparently, none of that troop was discovered by talent scouts or catapulted to stardom.

More than three decades later the city’s thespians raised the curtain for the Garland Civic Theatre, a non-profit group founded in 1968 with the lofty goal of “enhancing the quality of life for the citizens of the community through aesthetic experiences related to the Theatre arts.” News clippings show that within weeks after its February organizational meeting, promoted by Park Board Chairperson Vivian Yarborough, the Civic Theatre had acquired a part-time director from SMU’s drama department and was holding weekly workshops “to train its own actors, directors and technicians.” A bake sale in May of 1968 provided seed money for the troop’s July performance of “The Drunkard.”

As before, Garland’s aesthetic experiences of drama in the late 1960s occurred inside makeshift halls, which admitted adults for $1.25 and children for 50 cents. “The Drunkard” played for two weeks in H. B. Allard-provided commercial space at 903 State Street, described by GCT President Charles Roberts as sufficiently “rough-hewn” that “anyone seeing the production will recognize the theatre’s needs.” Subsequently, performances of other selections were held in a Methodist fellowship hall, the Granger Annex and the “Little Theater in the Park,” a 75-seat Central Park structure destroyed by fire in 1982.

But persistence paid off, and by the late 1970s GCT had acquired full-time services of a paid executive director. With the opening in downtown Garland of the Garland Performing Arts Center in 1983, the group finally found a proper showcase for its performances. GCT is now the major tenant of the facility, which affords both a 195- and a 719-seat theatre.

Today, theatre lovers enjoy comedy, drama, musical and mystery performances, as well as theatre classes in Garland, on a year-round basis. Four of the plays each year are staged by the Children on Stage program of GCT, which features performers between the ages of 8 and 18, working under the guidance of adult theatre professionals. Counting from both sides of the stage, the theater operation currently involves more than 22,000 people from Garland and the surrounding area.

To encourage broad participation, the theatre board sets ticket prices to cover approximately 60 per cent of operating costs from its $300,000 annual budget. The remainder of GCT’s support is gained from grants and contributions from individuals, corporations and public agencies.

Photo: (play cast only) courtesy Garland Civic Theatre.

In 1968 the Garland Civic Theatre staged its first performance, “The Drunkard,” featuring (l-r) Bob Thompson, Gary Record, Lewis Head (seated), Margo Hurley, David Alman, Deany Beale, William Salamon, Betty Wilhelm, Jo McMullen, and Carolyn Turnbull. The play was directed by Toni James, a drama student at the University of Texas at Austin.

- Details

From the Garland Local History & Genealogical Society, Volume 2-Number 2, June 1993

EARLY EDUCATION IN DALLAS COUNTY

Author: Unknown

We are indebted to Mr. Earnest Hill for procuring the following articles from the files in the Dallas County School Superintendent’s office:

“It would be very difficult to pinpoint a specific date on the calendar to mark the beginning of formal schooling in Dallas County. It is known however, that almost immediately after the creation of need to see to the education of their children (they) proceeded to do something about it. Much of this early teaching was done in the home by the mother or a neighbor even before the Commissioners Court legally accepted, on April 8, 1854, the responsibility for taking the scholastic census. The schooling, of course, was a community undertaking and cost no one anything.

There is considerable evidence which places a school near Lancaster as early as 1846. It was a one-room log cabin with a dirt floor. Farmer Branch, which boasted a blacksmith shop, a Baptist and a Methodist Church, and a post office; another of the progressive communities in Dallas County also had one of the earlier schools in the country.”

The following Historical Notes on Dallas County Schools, compiled by L.A. Roberts, read thusly.

“The first legislature of Texas created Dallas County on March 30, 1846.

Dallas County Commissioners Court officially authorized the location of land including three leagues on May 23, 1854.

Thirty-four school districts were created by the Commissioners Court (which) first made provisions for schools in the form of apportioning funds on September 23, 1858.

Dallas County issued the first teacher’s certificate on February 22, 1859, to W.H. Brundage.

The State Constitution of Texas was amended to permit the adoption of the District School System and the voting of local taxes for common school districts in 1883.

The School Law of 1884 created the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.

The County Superintendency was made optional in most populous counties in 1887.

*****

Mr. Hill was also able to get from the Dallas County Treasurer’s records data which shows that teacher’s salary vouchers were paid by the County Treasurer as shown by copies from the pages of the Treasurer’s ledger. These accounts were available for six of the eight schools we have researched and date from as early as 1885 to 1902 in some instances.

- Details

This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on Sept. 1, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

While times may have changed since the first beauty contest graced the annual Garland Jaycee Jubilee in 1953, the annual pageant still spotlights feminine charm. The rules are just different.

Inspiration for the event apparently jelled into action by mid-summer of 1953, as the local club leapt toward the front of the national pack from cities in its size class. Earlier that year both the Jaycees and the Jayceettes had won state awards for fundraising with the Labor Day Jubilees. At the 1953 national Jaycee convention in Chicago, President Dwight D. Eisenhower had presented the Garland group a second-place national award for the events.

With those records to match or beat, club members redoubled efforts for what they called a “top-notch entertainment program for the whole community.” Frequent front-page Garland News accounts kept readers abreast of unfolding developments, including plans for pony rides, a swimming contest, swimming exhibition, talent show, Fall Merchandise Parade for exhibiting local merchants, and a drawing for a new 1953 Plymouth sedan. To beef up manpower the club launched a summer membership campaign, which reportedly netted 55 new members within the first 10 days.

Long appreciative of prospects with a beauty contest, Garland Jaycee President W. E. Peavy, Jr. leaked news in August for naming a “Miss Garland Jaycee Jubilee of 1953.” Contest chairman Jack G. Smith soon provided details, stating that local commercial and industrial firms were encouraged to sponsor entrants, to be known as “Miss (business name, product or service).

Nancy Tuell, now Dr. Nancy Raines, a counselor at Southgate Elementary in Garland, won the contest that year, and still recalls the bare bones aspects of the first pageant. “Sponsors solicited the contestants, who were interviewed by the News for personal background,” she said, “and evaluated in swimsuit competition on Labor Day by a panel of three judges. Only a first place was selected, and the prize was a trophy. For all practical purposes, that was about it; the show was over.”

Besides Dr. Raines, who represented Intercontinental Manufacturing Co., where she worked then as a secretary, the six entrants and their sponsors for 1953 included Diane Dewit, Miss Rebuilders; Betty Kirgin, Miss Varo; Sylvia McMurray, Miss Downtown Merchants; Patsy Shearer, Miss Duck Creek Merchants and Ginger Tiemann, Miss Garland Shopping Center. Their ages ranged from 17 to 21 years, their heights from five-foot-two to five-foot-five inches and their weights from 105 to 117 pounds. No entry was recorded for the local meat-packing plant.

Mark Oleson, Jaycee coordinator for the 1995 pageant, hastens to point out that the event has matured considerably over the years from its fleshy roots in the ‘50's. At the end of each school year announcements are now mailed to each incoming junior female in the Garland school system, so that rehearsals for various contests may begin by the first of July. Those rehearsals help to prepare contestants for overall evaluations, consisting of talent, 25 %; interviewing, 25 %, scholarship, 20 %; and physical fitness, 15 %. The remaining 15 % of the total score rests on “presence and composure,” now involving an evening-gown competition to replace the one with bathing suits, which disappeared some 20 years back.

“Now we’re looking for ‘the girl next door,’ ” said Oleson, apparently thinking of a good neighborhood. When the five judges select her from among the 18 entrants, she will not only receive a trophy, but also a $750 cash scholarship, with smaller awards in descending amounts going to the first through fourth runners up. Additional scholarships are awarded for overall winners in each of the five evaluation categories.

Since 1972 the Garland affair has been affiliated with the Junior Miss pageants, allowing local winners to compete later on a statewide basis, and if successful there, on a national level as well.

Photo caption

Nancy Tuell, Miss Intercontinental Manufacturing Co., was selected Miss Garland Jaycee Jubilee of 1953 in the first of the Jaycee’s annual beauty contests.

Photo courtesy Nancy Raines.