This article originally appeared in the Garland/Mesquite section of The Dallas Morning News on April 21, 1995.

By Michael R. Hayslip

In one way or another Joe Craddock’s pickle factory turned everybody’s head when it to moved from Dallas to Garland in 1937.

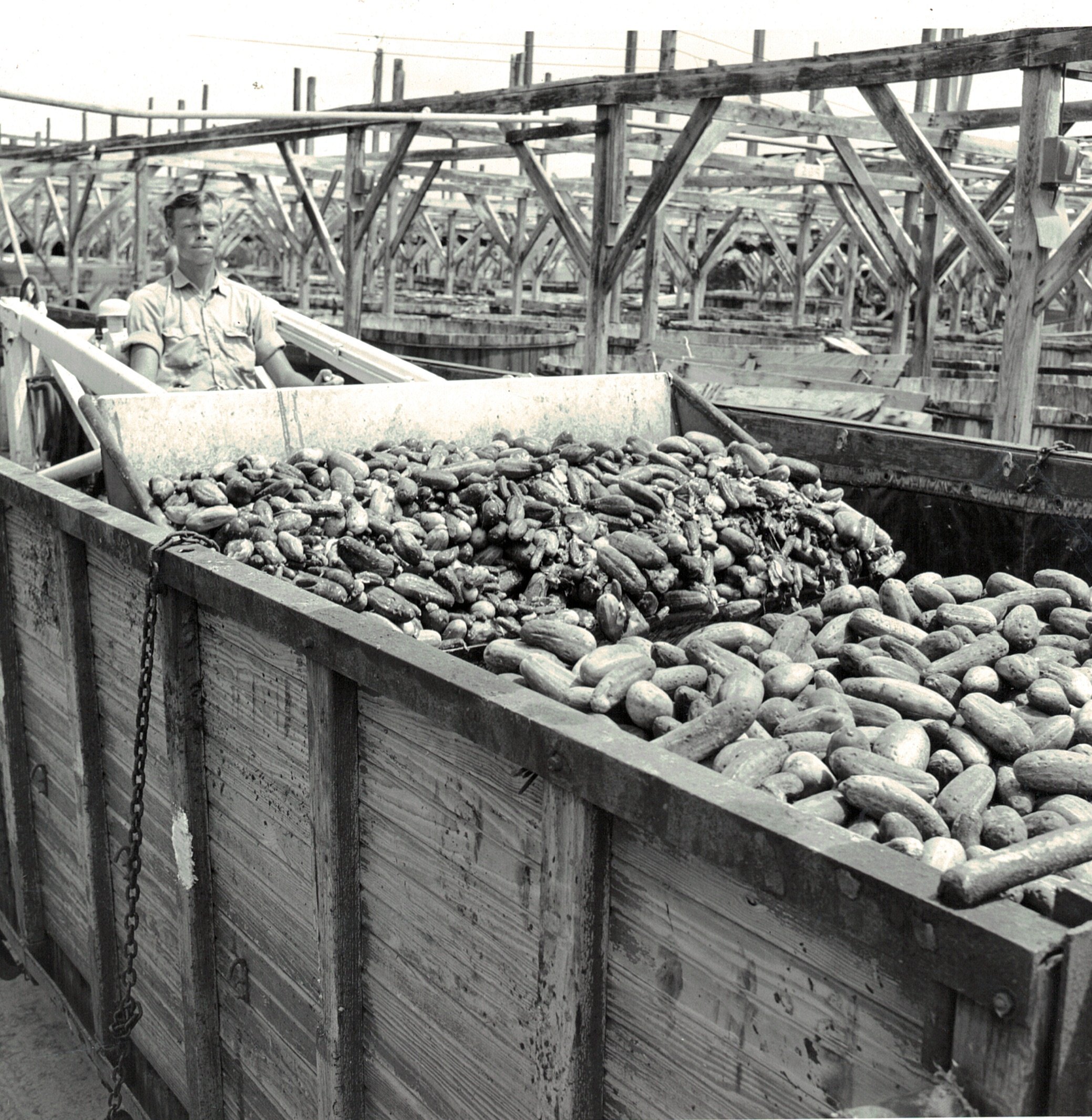

The $50,000 annual pickle payroll provided plums to pay the pipers of workers, businesses and their taxing authorities during lean times of the Depression. Utilizing the old facilities of the Garland Cotton Oil Mill beside the Katy tracks, the Craddock Food Manufacturing Company plant adjoined the Ferris Watson Seed Company installation to form an agribusiness industrial district at the north end of town -- Walnut Street.

Into this plant Craddock hauled pickling cucumbers, grown in various parts of Texas and Oklahoma for processing into dill, sour and sweet pickles, as well as relishes, marketed under the brand names of Betty Brand, Crispy and Crown .

On arrival the cucumbers were soaked in wooden vats with a brine of salt and water to create a “salt stock,” which could be processed into various flavors. After this initial step, which required at least six weeks, they were transferred to a series of other vats, containing vinegar for fermentation, alum for crispness, tumeric for even color and various flavoring spices for the desired effect..

According to Ralph Hammerle, “brewmeister” at the plant throughout the ‘50s, Craddock eventually boasted the world’s largest storage capacity, employing up to 40 full-time employees. In season, employment doubled.

More significant to some was the acrid aroma that drifted from the vats, averaging 700 bushels each, where tons of cucumbers lay in silent wait to become full-fledged pickles. Although some of these vats had been acquired from Anheuser Busch, their odor was not of beer, but of microorganisms produced by the pickle-making process. Carried along by prevailing southerly winds, this scent reminded everybody but Mr. Craddock, who lived in Dallas, that Garland was in the pickle business.

Had the vats remained open to the sky, sunlight would have diminished the stench and altered the character of the neighborhood. But rain would have also diluted the pickling solution, requiring frequent adjustment; therefore, the vats were covered as a matter of convenience.

Despite the malodorous aspects of the plant, as well as vat discharges onto open ground, new residential subdivisions were soon built north and west of it to alleviate the housing shortage caused by World War II. Grumbling, but grateful for a place to live, families quickly filled the homes. Some of them remained there until Morton Foods acquired the plant in the ‘60s and siphoned pickle production to their plant in Carrollton.

The pickle factory was razed to make room for Garland’s Main Post Office, dedicated in 1976. Soil tests prior to construction confirmed the historic account that the Post Office is perhaps the only one in the nation floating upon three decades of salt brine and pickle juice.

Photo caption:

A worker unloads cucumbers at the Craddock pickle plant, located where the Main Post Office now stands at Walnut and Newman Streets. (About 1945)